Behind the problems that routinely plague our organizations and leadership, you’ll find individuals who are either unwilling or unable to deal with broken promises. Colleagues break a rule, coworkers miss a deadline, friends fail to live up to commitments (or just plain behave badly), and nobody says a word. Nobody holds anyone accountable. With repeated infractions, individuals become increasingly upset until they finally do speak their minds, but they do so poorly–often creating whole new sets of problems.

Broken promises, missed deadlines, poor behavior–they don’t just make others’ lives miserable; they can sap up to 50 percent of organizational performance and account for the vast majority of divorces. Crucial Accountability offers the tools for improving relationships in the workplace and in life and for resolving all these problems–permanently.

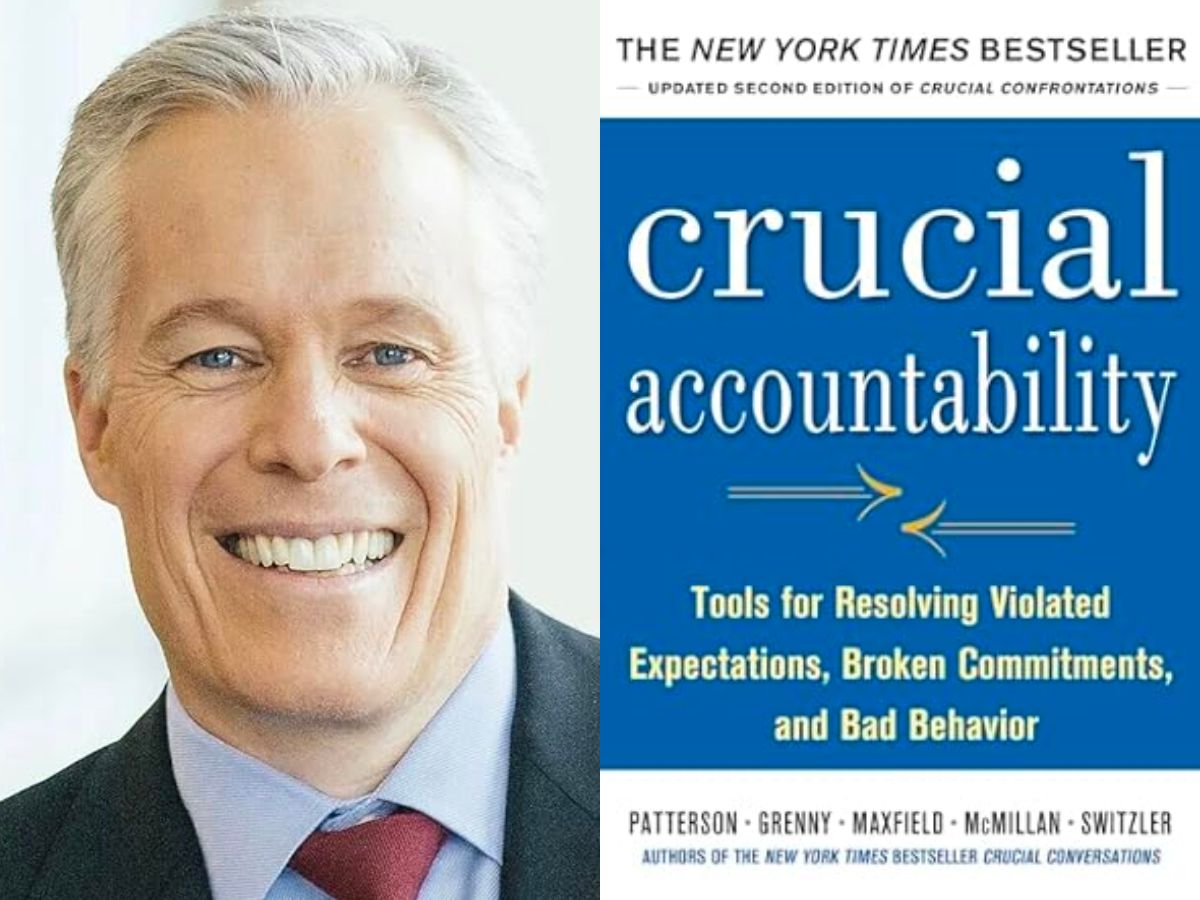

Crucial Acountability

Introduction:

In their insightful book, “Crucial Accountability: Tools for Resolving Violated Expectations, Broken Commitments, and Bad Behavior,” authors Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler offer a comprehensive guide to addressing accountability issues in both personal and professional spheres. Focusing on practical tools and strategies, the book provides valuable insights into fostering healthy relationships, promoting productivity, and building a positive organizational culture.

The Accountability Ladder:

One of the central concepts introduced in the book is the Accountability Ladder. This model delineates various levels of accountability, ranging from avoiding responsibility to proactively taking steps to solve problems. By understanding these levels, individuals can assess their own behavior and that of others, fostering a culture of ownership and accountability.

The See-Hear-Feel Model:

Effective communication is pivotal in addressing accountability challenges, and the See-Hear-Feel Model serves as a valuable framework. This tool encourages individuals to express observations, thoughts, and emotions in a non-confrontational manner, facilitating open dialogue and understanding.

The Six-Source Model:

To identify the root causes of accountability issues, the authors present the Six-Source Model. This framework explores personal motivation, ability, role clarity, task clarity, external motivation, and cultural norms as contributing factors. By pinpointing these sources, individuals can address the underlying issues that lead to broken commitments and unmet expectations.

The State My Path Model:

Expressing concerns and expectations effectively is a key aspect of accountability. The State My Path Model provides a structured approach to communication, enabling individuals to convey their thoughts while maintaining a focus on mutual purpose and respect. This tool empowers individuals to navigate difficult conversations with clarity and empathy.

The Decision Tree:

When faced with accountability challenges, individuals often grapple with the appropriate course of action. The Decision Tree introduced in the book serves as a practical guide, helping individuals choose between dialogue, confrontation, or a combination of both. This tool assists in making informed decisions that align with the desired outcomes.

Real-Life Examples:

“Crucial Accountability” enriches its concepts by illustrating them through real-life examples and case studies. These anecdotes provide readers with practical insights into applying the tools and strategies in diverse situations, making the book relatable and actionable.

Conclusion:

“Crucial Accountability” stands as a valuable resource for anyone seeking practical approaches to address accountability issues. By offering a toolkit of strategies, models, and frameworks, the authors empower individuals to foster accountability, enhance communication, and build stronger relationships in both personal and professional spheres. With its focus on tangible tools and real-world applications, the book equips readers with the skills needed to navigate challenges and promote positive change.

Part A: Work on Me First: What to do BEFORE a Crucial Accountability Discussion

Chapter 1: Choose What and If: How to know what conversation to hold & if you should hold it

Main Idea:

In Chapter 1 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler, the authors set the stage by introducing the concept of crucial conversations and emphasizing their profound impact on personal and professional spheres. The central idea is to explore the significance of dialogue in navigating challenging discussions and understanding why mastering crucial conversations is essential for effective communication.

Key Concepts:

- Defining Crucial Conversations: The chapter defines crucial conversations as discussions where stakes are high, opinions vary, and emotions run strong. Identifying these moments is crucial for addressing them effectively.

- Impact on Results: The authors stress the direct correlation between one’s ability to handle crucial conversations and the impact on results. Successful conversations lead to better outcomes, while mishandled discussions can have detrimental consequences.

- The Four Crucial Conversations Skills: The chapter introduces four skills essential for mastering crucial conversations: noticing when a conversation becomes crucial, holding a high-stakes conversation without avoiding it, turning emotions into effective dialogue, and achieving the desired results.

- Common Crucial Conversations: Examples of crucial conversations in various contexts are presented, ranging from negotiations and performance reviews to addressing behavioral issues or dealing with team conflicts.

Case Study:

Imagine a seasoned business executive, Sarah, preparing for a crucial meeting with stakeholders to discuss a project’s unforeseen challenges. Sarah, aware of the importance of mastering crucial conversations, diligently applies the principles outlined in Chapter 1.

As the meeting unfolds, she keenly observes the signs of a crucial conversation—the high stakes, differing opinions, and heightened emotions among team members. Drawing from the chapter’s insights, Sarah doesn’t shy away from addressing the challenging issues head-on.

Remembering the four crucial conversation skills, Sarah navigates the dialogue with finesse. She starts with heart, ensuring the team stays focused on the common goal. Sarah actively listens to diverse opinions, acknowledging the varying perspectives and making everyone feel heard and valued.

During moments of tension, Sarah applies the “Learn to Look” principle, noticing when safety is at risk and taking corrective action to maintain a constructive atmosphere. Implementing the “Make It Safe” approach, she encourages open discussion, assuring her team that it’s safe to voice concerns and suggestions.

To manage her own emotions, Sarah employs the “Master My Stories” technique, staying calm and composed even when faced with criticism. Applying the principles of crucial conversations, Sarah leads the team towards a collaborative resolution.

As the meeting concludes, it becomes evident that Sarah’s mastery of crucial conversations has not only averted potential conflicts but has also set the stage for effective problem-solving. The project moves forward with a shared understanding, showcasing the tangible impact of mastering crucial conversations in the business realm.

In conclusion, Chapter 1 lays the foundation for the importance of mastering crucial conversations, providing a roadmap for navigating high-stakes discussions in the complex landscape of business. It serves as a precursor to the practical tools and strategies introduced in subsequent chapters, offering invaluable insights for leaders.

Chapter 2: Master My Stories: How to get your head right before opening your mouth

Main Idea:

Chapter 2 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler delves into the heart of effective communication—mastering crucial conversations through the power of dialogue. The main idea revolves around understanding and harnessing the transformative potential of dialogue to navigate high-stakes discussions successfully.

Key Concepts:

- Dialogue as a Transformative Tool: The chapter emphasizes that dialogue is not just about talking; it’s a transformative tool that, when used skillfully, can reshape relationships and outcomes. It explores how meaningful conversations can lead to shared understanding and collaboration.

- The Path to Dialogue Mastery: Four key components are introduced as the path to mastering dialogue: establishing mutual purpose, creating mutual respect, achieving a free flow of meaning, and making decisions together. These components lay the groundwork for productive and impactful conversations.

- Mastering Your Stories: Building on the concept introduced in the previous chapter, this chapter explores in-depth the role of personal narratives in shaping dialogue. It provides insights into identifying and reframing unproductive stories, allowing individuals to engage in more constructive conversations.

- The Power of Silence: The chapter highlights the importance of silence as a powerful tool in dialogue. Strategic pauses can create space for reflection, defuse tension, and invite others to contribute, enhancing the overall quality of the conversation.

Case Study:

Consider a scenario where a project team, led by Alex, faces a critical crossroads due to differing opinions on the project’s strategic direction. Drawing from the principles introduced in Chapter 2, Alex approaches the situation with a focus on mastering crucial conversations through dialogue.

Recognizing the need for mutual purpose, Alex starts the meeting by clarifying the team’s shared goals and aligning everyone toward a common objective. This sets the stage for a conversation where team members feel a collective sense of purpose.

Throughout the dialogue, Alex places a strong emphasis on creating mutual respect. Acknowledging diverse perspectives and encouraging team members to express their views fosters an atmosphere of respect and openness. The team begins to appreciate each other’s insights, laying the foundation for collaborative decision-making.

As the conversation unfolds, Alex skillfully navigates towards achieving a free flow of meaning. By encouraging transparent communication and addressing potential misunderstandings, the team engages in a more meaningful exchange of ideas. This ensures that everyone’s input is considered, enhancing the richness of the dialogue.

Understanding the power of silence, Alex strategically introduces pauses during moments of tension. These pauses allow team members to reflect on the discussion, diffuse any escalating emotions, and encourage thoughtful contributions.

By the end of the dialogue, the team collectively makes decisions that incorporate the best aspects of each perspective. The project not only stays on course but also benefits from the synergy generated through the mastery of crucial conversations.

In conclusion, Chapter 2 underscores the transformative power of dialogue in mastering crucial conversations. It provides MBA students and business professionals with practical insights into creating purposeful, respectful, and meaningful conversations that can drive positive outcomes in complex business scenarios.

Part B: Create Safety: What to do DURING a Crucial Accountability Discussion

Chapter 3: Describe the Gap: How to start an Accountability Discussion

Main Idea:

Chapter 3 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler introduces the pivotal concept of “Starting with Heart.” The main idea revolves around the critical importance of staying focused on one’s real goals and intentions during crucial conversations. It provides insights into the role of personal motivation and maintaining clarity about the desired outcomes.

Key Concepts:

- The Role of Intentions: The chapter underscores that the key to successful crucial conversations lies in understanding and aligning with one’s true intentions. By starting with heart, individuals can avoid being sidetracked by emotions and conflicts and remain focused on achieving positive outcomes.

- Identifying Your Contribution: It encourages self-reflection to identify one’s contribution to the conversation. Recognizing personal biases and understanding how they may impact the dialogue is crucial for effective communication.

- Staying Focused on Mutual Purpose: Establishing mutual purpose, a shared goal that aligns all parties involved, becomes a guiding principle. It serves as a compass for the conversation, ensuring that discussions remain constructive and aimed at achieving common objectives.

- Mastering My Stories in Dialogue: Building on the concept introduced earlier, the chapter explores how personal narratives, or “stories,” can either enhance or hinder dialogue. It provides strategies for reframing unproductive stories, allowing individuals to approach conversations with a more positive mindset.

Case Study:

Meet Emma, who is leading a Team through a critical product launch. As the launch date approaches, tension rises due to differing opinions on the marketing strategy. Drawing from the principles in Chapter 3, Emma approaches the situation by starting with heart.

Emma takes a moment for self-reflection, identifying her own biases and acknowledging the potential impact on the conversation. Recognizing her intention to ensure the success of the product launch, she consciously sets aside personal emotions and focuses on the team’s collective goal.

During the crucial conversation, Emma initiates by establishing mutual purpose. She articulates the shared objective of delivering a successful product to the market, ensuring that everyone understands the overarching goal. This not only aligns the team but also diffuses initial tension.

Applying the concept of “Mastering My Stories,” Emma identifies potential misinterpretations and reframes unproductive narratives. Rather than assuming resistance from certain team members, she opens the floor for discussion, encouraging diverse perspectives and creating an atmosphere of collaboration.

As the dialogue progresses, Emma consistently brings the focus back to mutual purpose. Whenever the conversation veers toward conflict, she steers it back by reminding everyone of the common goal. This strategic approach helps the team stay on track and maintain a constructive dialogue.

By the end of the conversation, the team has not only resolved their differences but has also developed a more robust marketing strategy. Emma’s adept application of “Starting with Heart” has not only fostered a positive work environment but has also contributed to the overall success of the product launch.

Chapter 4: Make It Motivating: How to help others want to take action

Main Idea:

Chapter 4 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan & Al Switzler introduces the crucial concept of “Learn to Look.” The main idea revolves around the ability to notice when safety is at risk during crucial conversations. It explores the role of non-verbal cues, individual behaviors, and environmental factors in identifying signs that the conversation is veering away from a constructive path.

Key Concepts:

- The Importance of Safety: The chapter underscores that creating a safe environment is paramount for effective communication. When individuals feel unsafe, they are less likely to engage openly and honestly in crucial conversations, hindering the potential for positive outcomes.

- Non-Verbal Cues: Learn to Look emphasizes paying attention to non-verbal cues such as body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions. These cues provide valuable insights into the emotional state of the participants and can signal when safety is at risk.

- Environmental Factors: The chapter explores how the physical environment can impact the safety of a conversation. Factors such as seating arrangements, office settings, and even cultural differences can influence the comfort level of individuals engaged in a dialogue.

- Monitoring Conversations in Real Time: Learn to Look encourages individuals to actively monitor conversations in real time. By staying vigilant to signs of discomfort or defensiveness, participants can address safety concerns promptly, preventing the escalation of conflicts.

Case Study:

Consider Sarah, an MBA student working on a group project with team members from diverse cultural backgrounds. As the project evolves, tensions arise during crucial discussions about project timelines and responsibilities. Sarah, aware of the principles from Chapter 4, takes a proactive approach to Learn to Look.

During a team meeting, Sarah observes non-verbal cues indicating discomfort among certain team members. Some members exhibit defensive body language, and the overall tone of the conversation becomes strained. Recognizing these signs, Sarah realizes that safety is at risk in the dialogue.

Instead of ignoring these cues, Sarah decides to address them directly. She pauses the discussion and acknowledges the tension in the room. By creating an open and non-judgmental space, she encourages team members to express their concerns and perspectives freely.

Sarah also considers environmental factors, noting that the team’s seating arrangement may contribute to the discomfort. She suggests a more informal setting for future discussions, fostering a collaborative atmosphere that puts everyone at ease.

By actively monitoring the conversation in real time, Sarah navigates potential conflicts with finesse. As a result, the team regains a sense of safety in their dialogue, allowing them to refocus on the project’s objectives. Sarah’s Learn to Look approach not only defuses immediate tensions but also establishes a foundation for more open and constructive communication within the team.

In conclusion, Chapter 4 provides valuable insights into the critical skill of Learn to Look. By understanding the importance of safety, recognizing non-verbal cues, considering environmental factors, and monitoring conversations in real time, MBA students and business professionals can create environments conducive to effective crucial conversations, ultimately fostering positive outcomes in diverse and challenging situations.

Chapter 5: Make It Easy: How to make keeping commitments (almost) painless

Main Idea:

Chapter 5 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan & Al Switzler introduces the central concept of “Make It Safe.” The main idea revolves around the crucial role of psychological safety in fostering open dialogue during crucial conversations. It explores strategies for creating an environment where individuals feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and concerns without fear of negative consequences.

Key Concepts:

- The Foundation of Dialogue: Make It Safe underscores that psychological safety is the foundation of effective dialogue. When individuals feel safe expressing themselves, they are more likely to contribute openly and honestly to the conversation.

- Mutual Purpose and Mutual Respect: The chapter emphasizes the dual importance of establishing mutual purpose and mutual respect to create safety in dialogue. Mutual purpose aligns participants toward a common goal, while mutual respect ensures that each individual’s perspective is valued.

- Clarifying Intentions: Make It Safe encourages participants to clarify their intentions and affirm a shared commitment to a positive outcome. This transparency helps build trust and reassures others that the conversation is constructive and not intended to harm.

- Applying the AMPP Model: The AMPP model (Ask, Mirror, Paraphrase, Prime) is introduced as a tool for fostering safety in conversations. This model provides practical steps for creating an atmosphere of trust and openness.

Case Study:

Imagine Jake, who finds himself in a crucial conversation with another team member, Lisa, who has been consistently missing project deadlines. Recognizing the principles from Chapter 5, Jake applies the Make It Safe concepts to navigate the discussion effectively.

As the conversation begins, Jake takes a moment to establish mutual purpose. He clarifies that their shared goal is the success of the project and emphasizes that the dialogue is aimed at finding solutions, not assigning blame. This sets a positive tone for the conversation.

To ensure mutual respect, Jake acknowledges Lisa’s contributions to the project and expresses appreciation for her efforts. This reassures Lisa that her perspective is valued, making her more receptive to the upcoming discussion.

Jake then applies the AMPP model. He starts by asking Lisa about her perspective on the project challenges. Mirroring her emotions and concerns, Jake shows empathy and understanding. He paraphrases Lisa’s points to confirm his understanding and primes the conversation by expressing his commitment to working collaboratively on solutions.

Throughout the dialogue, Jake consistently reinforces the safety of the conversation by reiterating their mutual purpose and respect. This approach allows Lisa to openly share her challenges, and together, they identify actionable steps to address the project issues.

By the end of the conversation, Jake and Lisa not only resolve the immediate project concerns but also strengthen their working relationship. Jake’s application of Make It Safe principles demonstrates how creating a psychologically safe environment can lead to productive and collaborative crucial conversations.

Chapter 6: Stay Focused and Flexible: What to do when others get sidetracked, scream, or sulk

Main Idea:

Chapter 6 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan & Al Switzler introduces the crucial concept of “Master My Stories.” The main idea revolves around understanding and managing the personal narratives or stories we create during crucial conversations. It emphasizes how our interpretations and assumptions can impact our emotions and behaviors, and, consequently, the outcome of the conversation.

2. Summary of Key Concepts and Takeaways from the Chapter:

- The Stories We Tell: The chapter highlights that during crucial conversations, individuals often create stories to make sense of situations. These stories are interpretations of events and can influence emotions and subsequent actions.

- Recognizing Unproductive Stories: Master My Stories encourages individuals to become aware of unproductive stories—ones that may be based on assumptions, judgments, or incomplete information. Identifying these stories is the first step toward managing them effectively.

- Reframing and Revising Stories: The chapter provides strategies for reframing unproductive stories. By challenging assumptions, seeking additional information, and considering alternative perspectives, individuals can revise their stories to be more constructive and accurate.

- Avoiding the Victim-Villain-Hero Cycle: Individuals often cast themselves as victims, others as villains, and sometimes even themselves as heroes in their stories. Master My Stories guides individuals in breaking this cycle by focusing on understanding and collaboration rather than blame.

3. A Story Explaining All the Key Learnings from the Chapter:

Imagine Alex, leading a team project. During a crucial meeting, tensions rise as team members debate the allocation of tasks. In the heat of the conversation, Alex perceives criticism from a team member, Lisa, as an attack on his leadership.

Applying the principles from Chapter 6, Alex becomes aware of the story forming in his mind—that Lisa is undermining his authority. Recognizing this unproductive story, Alex takes a step back and reframes his perspective. Instead of viewing Lisa as a villain, he considers that her comments might stem from a desire for project success.

During the conversation, Alex actively listens to Lisa’s concerns, seeking clarification rather than assuming malicious intent. This simple shift in mindset helps Alex revise his story, seeing Lisa not as a critic but as a collaborator with valid perspectives.

As the team discusses solutions, Alex consciously avoids the victim-villain-hero cycle. Rather than positioning himself as the victim of criticism or casting Lisa as the villain, he focuses on shared goals and finding a collaborative way forward.

By the end of the meeting, the team not only resolves the task allocation issue but also strengthens their collaboration. Alex’s application of Master My Stories not only prevents a potential conflict but also fosters a more positive and productive team dynamic.

In conclusion, Chapter 6 provides valuable insights into the impact of personal narratives on crucial conversations. By recognizing, reframing, and revising unproductive stories, individuals can navigate emotional terrain more effectively, fostering a constructive environment for dialogue and collaboration in the complex landscape of business interactions.

Part C: Move to Action: What to do AFTER a Crucial Accountability Discussion

Chapter 7: Agree on a Plan and Follow Up: How to gain commitment and move to action

Main Idea:

Chapter 7 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan & Al Switzler introduces the central concept of “STATE My Path.” The main idea revolves around mastering the art of persuasive communication during crucial conversations. It provides a framework for individuals to express their thoughts effectively, without triggering defensiveness, and with the precision needed to navigate challenging discussions.

Key Concepts:

- The Importance of Persuasion: The chapter emphasizes that the ability to persuade others is crucial in crucial conversations. Persuasion involves expressing thoughts clearly, convincingly, and respectfully, fostering an environment where others are more likely to be open to different perspectives.

- The STATE Model: STATE is introduced as a model for persuasive communication, comprising five key elements: Share your facts, Tell your story, Ask for others’ paths, Talk tentatively, and Encourage testing. These elements provide a structured approach to expressing thoughts while maintaining a positive tone.

- Sharing Facts and Telling Stories: Balancing the presentation of facts with personal narratives is crucial. While facts provide objectivity, stories add a human element to the communication, making it relatable and emotionally resonant.

- Asking for Others’ Paths: Actively seeking others’ perspectives is a key component of effective communication. Understanding their viewpoints not only demonstrates respect but also contributes to a more comprehensive and collaborative decision-making process.

Case Study:

Meet Jessica, leading a team project. During a crucial meeting, tensions arise regarding the project timeline. Applying the principles from Chapter 7, Jessica navigates the conversation using the STATE model.

As the discussion begins, Jessica starts by sharing facts about the project timeline, presenting objective data to establish a common understanding. Simultaneously, she tells a story about the challenges the team has faced, adding a personal touch to the information.

Jessica then asks for others’ paths, actively seeking input from team members. This not only acknowledges the value of their perspectives but also contributes to a more inclusive decision-making process. By understanding others’ viewpoints, Jessica can address concerns and incorporate diverse ideas into the conversation.

Throughout the dialogue, Jessica talks tentatively, using a tone that is both assertive and respectful. This helps to avoid triggering defensiveness among team members and creates an atmosphere conducive to open communication.

To encourage testing, Jessica invites feedback and suggestions from the team, fostering a collaborative environment. This not only empowers team members but also contributes to the overall quality of the decision-making process.

By the end of the meeting, the team reaches a consensus on adjusting the project timeline. Jessica’s application of the STATE model not only persuades team members but also strengthens their collaborative dynamics. The project moves forward with a shared understanding, highlighting the efficacy of persuasive communication in crucial conversations.

In conclusion, Chapter 7 provides valuable insights into the art of persuasion with the STATE My Path model. By effectively sharing facts, telling stories, asking for others’ paths, talking tentatively, and encouraging testing, individuals can navigate crucial conversations with precision and foster an environment of open and collaborative communication, ultimately contributing to positive outcomes in various business scenarios.

Chapter 8: Put It All Together: How to solve big, sticky, complicated problems

Main Idea:

Chapter 8 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan & Al Switzler introduces the pivotal concept of “Explore Others’ Paths.” The main idea revolves around the art of active listening during crucial conversations. It emphasizes the significance of understanding others’ perspectives, acknowledging emotions, and fostering an environment of genuine empathy.

Key Concepts:

- The Importance of Listening: The chapter underscores the crucial role of active listening in effective communication. By truly understanding others’ viewpoints, individuals can build trust, enhance collaboration, and contribute to positive outcomes in crucial conversations.

- The Explore Others’ Paths Model: The chapter introduces a model for exploring others’ paths, emphasizing the need to listen empathetically, validate emotions, and encourage the expression of differing opinions. This model provides a structured approach to understanding and appreciating diverse perspectives.

- Empathy and Validation: The chapter highlights the significance of empathy in communication. Acknowledging and validating others’ emotions fosters a sense of understanding and helps create an atmosphere where individuals feel heard and respected.

- Encouraging Differing Opinions: Actively seeking out and encouraging differing opinions contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the situation. This approach not only enriches the dialogue but also promotes a collaborative problem-solving process.

Case Study:

Imagine Michael, leading a team project where conflicts arise due to differing opinions on the project approach. Applying the principles from Chapter 8, Michael navigates the conversation using the Explore Others’ Paths model.

As the discussion unfolds, Michael actively listens to his team members, seeking to understand their perspectives. He empathetically acknowledges their concerns, validating the emotions behind their opinions. This creates a space where team members feel heard and respected, laying the groundwork for open communication.

Using the Explore Others’ Paths model, Michael encourages team members to express their differing opinions. Rather than dismissing these perspectives, he values the diversity of ideas, recognizing that each viewpoint contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the project challenges.

Throughout the dialogue, Michael remains focused on empathy and validation. He genuinely acknowledges the emotions expressed by team members, reinforcing a sense of understanding and trust. This approach not only diffuses potential conflicts but also contributes to a more positive team dynamic.

By the end of the meeting, the team reaches a consensus on a modified project approach that incorporates diverse perspectives. Michael’s application of the Explore Others’ Paths model not only resolves conflicts but also strengthens the collaborative spirit within the team. The project moves forward with a shared vision, highlighting the power of active listening in crucial conversations.

In conclusion, Chapter 8 provides invaluable insights into the art of active listening through the Explore Others’ Paths model. By empathetically listening, validating emotions, and encouraging differing opinions, individuals can navigate crucial conversations with a focus on understanding and collaboration, ultimately contributing to positive outcomes in diverse business scenarios.

Chapter 9: The 12 “Yeah-Buts”: How to deal with the truly tough

Main Idea:

Chapter 9 of “Crucial Accountability” by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler introduces the transformative concept of “Move to Action.” The main idea centers around the transition from dialogue to concrete action in crucial conversations. It emphasizes the importance of converting discussions into measurable and effective outcomes, ensuring that positive change results from the dialogue.

Key Concepts:

- Linking Dialogue to Results: The chapter underscores the critical need to translate the insights gained from crucial conversations into tangible actions. While dialogue is essential for understanding, the ultimate goal is to drive change and achieve positive outcomes.

- Creating Clear Expectations: Move to Action emphasizes the importance of setting clear expectations and commitments. Establishing specific and achievable goals ensures that everyone involved in the conversation understands their role in implementing the agreed-upon solutions.

- Follow-Up and Accountability: Effective implementation requires follow-up and accountability. The chapter introduces strategies for monitoring progress, addressing obstacles, and holding individuals accountable for their commitments. This ensures that the desired change is not only initiated but sustained over time.

- Continuous Improvement: Move to Action encourages a mindset of continuous improvement. By assessing the effectiveness of implemented solutions, individuals can refine their approaches, learn from experiences, and contribute to ongoing positive change.

Case Study:

Meet Rachel, a new Leader who is tasked with leading a team through a critical project deadline. As the project progresses, Rachel identifies potential risks and conflicts within the team. Applying the principles from Chapter 9, Rachel seamlessly transitions from dialogue to action.

During a team meeting, Rachel discusses the identified challenges openly with the team. Together, they engage in a crucial conversation, exploring different perspectives and potential solutions. As the dialogue unfolds, Rachel skillfully guides the team toward specific and actionable commitments.

The Move to Action approach involves setting clear expectations. Rachel ensures that each team member understands their role and responsibilities in addressing the identified challenges. Clear timelines and deliverables are established, creating a roadmap for implementation.

Rachel recognizes the importance of follow-up and accountability. Regular check-ins are scheduled to monitor progress, address any obstacles, and provide support where needed. This proactive approach ensures that the agreed-upon solutions are not only initiated but also progressing toward successful implementation.

As the project deadline approaches, Rachel reflects on the outcomes achieved through the Move to Action strategy. The team has successfully navigated challenges, met project milestones, and strengthened their collaborative dynamics. The continuous improvement mindset is applied, with Rachel leading a debrief session to capture lessons learned and identify opportunities for future enhancements.

In conclusion, Chapter 9 provides MBA students and business professionals with a roadmap for turning dialogue into concrete action. By creating clear expectations, ensuring follow-up and accountability, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement, individuals can drive positive change and achieve meaningful results in the complex landscape of business challenges and projects.